Most software today is very much like an Egyptian pyramid with millions of bricks piled on top of each other, with no structural integrity, but just done by brute force and thousands of slaves - Alan Kay

I am perplexed about the sudden and continuous development of civilization, given the absurdly high complexity permeating our everyday lives. Yet, we rarely notice how complicated everything is. Consider for a minute: when driving, your foot is influencing thousands of explosions per minute. Or when clicking the volume button in your TV remote, millions of electronic instructions are taking place. Endless iterations have gone by in centuries around the world to bring us the stoves in our kitchens, yet heating milk looks mundaine.

Or, yet, you board an airplane, sit comfortably, and arrive a few hours later on the other side of a sphere floating around a burning star. How many million hours of work have gone into developing something that is heavier than air and faster than sound. That is out of sight and our brain is looking for the button to recline the seat to enjoy a movie.

We experience simplicity because we only look at the surface in front of us. Beneath, however, are layers and layers of gradual and hierarchical complexity. The hood, the components, the engine, the mechanisms inside, the spark plug, the camshaft, and the descent into physics and chemistry. It’s fractals of black boxes all the way down.

The good news is that we can use the principle of progressive compartment to manage most complexity, making maintenance and innovation simpler in many areas of life. These black boxes reduce the need to think about what is out of sight until we have to. What we experience is gradual layering. Like russian dolls.

In education, one starts with the foundations, then moves on to harder topics. First you learn to read, then you learn to write. In real state, first you research by geography and price, then you move on to the specifics. In software, you don’t put the what and the how in the same level. In a book, you first have the index, then the chapters, then concepts laid out gradually in paragraphs.

This is the art of making complex things simple and hard things easy. Flat hierarchy tends to produce more complexity, but compartments help contain entropy.

Tiny Tiny Machines

Biology inspired engineers to think about components as cells, or objects. When engineers at Xerox PARC in 60’s and 70’s envisioned an electronic board as composed of interdependent, tiny little machines communicating among themselves, it opened a door into a future that incredibly vast (but in great part is still waiting to happen).

The greatest system to have flourished from this framework is the Internet itself. Peers anywhere on the planet are able to send and receive messages through millions of network nodes. This cell-like architecture enabled the countless revolutions we have experienced.

The cell membrane separates and protects its interior from the environment. The many different types of specialized cells cooperate with each other by passing materials around. Alan Kay argued that applying these concepts to human-made systems, making objects bounded by these characteristics, “messaging, local retention and protection and hiding of state”, would yield better and more robust systems.

Object orientation is a mental model about the world. It segregates components and hides their complexity by abstracting away their internals, like small black boxes. Information about the system is compacted, and the brain can scale reasoning step by step. It is a recipe for simplifying all areas of life, from your to-do app (with areas and projects and tasks and subtasks) to banks, from real state to engineering.

Software

At the root, object orientation had no relation to programming languages. It was always about the messages components exchange. Whatever the paradigm, the value is in managing the application’s state and structures in a way that is self-contained.

Classes, inheritance, mutability versus immutability, came to be associated with it decades later, with C++ and later Java. The debate, object orientation versus functional languages, has always been moot because you can have boundaries in any paradigm. When asked what languages could apply it, Alan Kay’s replied, “Lisp”.

Take Erlang, a functional language. Each BEAM process is a functional program getting a stream of messages. Outside a particular process there could be all sorts of chaotic occurrences, a storm raging, but we do not care. The compartmentalization lets us focus on what individual components need to do and only that.

In 1969, Smalltalk was born as a project to create a programming language based on these principles. C++ (1983) and Java (1995) are the most famous, although not the most representative. When asked about C++, Kay replied, “actually I made up the term object-oriented, and I can tell you I did not have C++ in mind”.

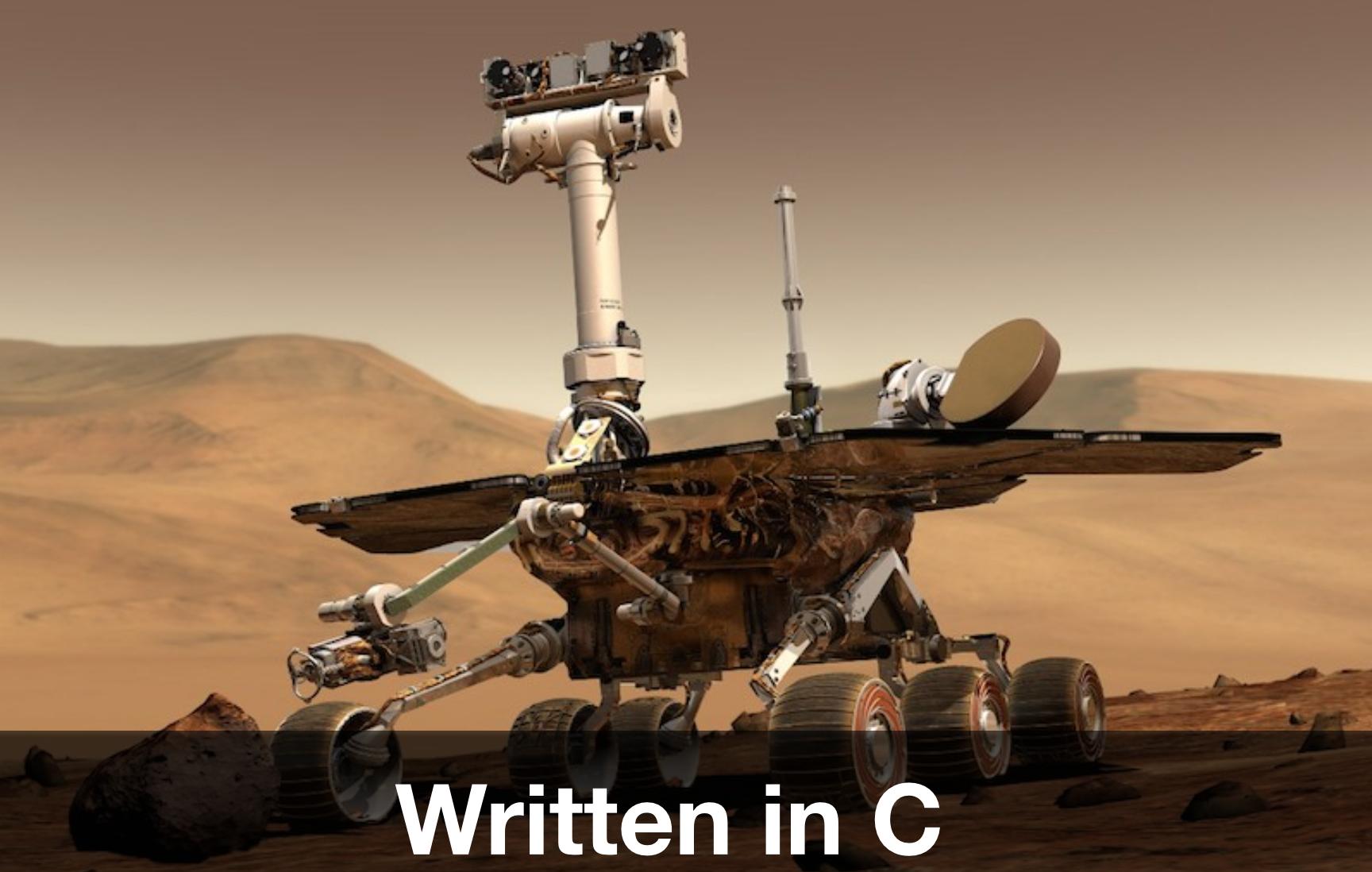

Curiosity Mars Rover

Curiosity Mars Rover is a great example of system built with object orientation in mind. Written in C, it applies the concepts information hiding and boundaries to contain its complexity.

Curiosity has over 2.5 millions lines of code. Composed of many modules, they use a message queue written specially for the rover. Whenever a module needs an information or something to be done, messages go into the queue, which will dispatch it to the target module, which will then execute what’s needed. There are no mutexes, no transactional memory.

If a message is a command, module A never expects an answer or return value from the receiving module B because they are independent. If module B breaks or goes offline, module A is never impacted by it. If it’s a query message, then a return value is expected but no state can be changed.

Besides the evident robustness, this decouples module A from module B. There are no setters. When working on a module, you are not required to know how another module works. Cognitive load is lower. Different teams can comply with a contract of how the interfaces are designed and work in parallel. Debugging gets easier because you can apply binary search to figure out which modules are the root cause.

Changing the system is easier due decoupling, provided changing one part of the system won’t require you to change anything else. Like in Erlang, processes are deployed to production independently while other components continue running. From another angle, NASA basically rewrote Erlang in C. And as Joe Armstrong once jokingly said,

Erlang might be the only object oriented language.

A Fractal of Perspectives

The principle of black boxes can be applied to distributed systems, microservices, text codebases, and even Unix pipes. In code, we tend to use namespaces to convey components, hide states from other components and see methods as representations of messages.

All systems have some coupling, some level of complexity and an unescapable cognitive burden. It’s our responsibility, however, to manage it.