There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

Phil Karlton

We all want to read and understand software. We want code to make sense, to speak the language of the business model, to convey meaning and relationships with clarity. Although code is written once, it is read many times.

Bad code confuses us. Bad code codifies assumptions that make sense for the writer but not for the readers. Have you ever needed help to understand a piece of code? Have you ever been demanded disproportionate energy and effort to make sense of what code was doing? That’s bad code.

But how do we go from bad to good?

The first step to succeed in any area is a solid understanding of its elements and their impact on other people and the environment. Good movie directors internalize elements and patterns after watching movies for countless hours, then manipulate them to tell stories effectively. The same can be said for novelists, musicians, chess players.

Similarly, a software developer should be able to scan a business domain and discover its elements and patterns. Some are obvious, some are not, and this is where it gets tricky: finding names for some of these elements is not a trivial task. Some elements don’t exist in the real world, some do but lack names everyone will understand. Some relationships are inevitable for the success of the business domain but were never discussed by the business owners.

Some names individualize elements whereas others aggregate them. Some reveal abstract symbols (graphs and nodes) whereas others make things concrete (cabled network and hubs). Some reveal roles (the administrators table), some reveal usage (users table), some reveal nature (people table). Some names don’t identify elements at the right level of precision (document vs XML), whereas some conflate multiple elements into one. Some just lack inspiration.

Good writing, as it turns out, is about optimizing for ease of reading.

Naming Components and Elements

There’s a whole universe of types of relationships among elements. Some things live side by side (e.g nodes), some contain others (organization vs employees). Some things depend on others (purchases and payments methods) while some generate others (bills and installments).

To uncover concepts and their names, we start out by asking simple questions, as if to prove that they make sense at all.

To illustrate our first concept, let’s start simple. Given the picture below, what room is this?

Question 1 of 3

Judging from this furniture, this is very likely to be a living room. Based on a component, we know the name of the room we’re in. That was easy. Next.

Question 2 of 3

Based on this object, we can fairly sure say that this is the restroom.

See a pattern here? The name of the room is a label that defines what is inside of it. With that label we don’t need to look inside the container to know what elements are there. That enables us to establish our first corollary:

Corollary 1: container name is a function of its elements.

Note it is basically Duck Typing. Does it have a bed? Then it’s probably a bedroom.

Now, the opposite is also true: based on the container name we can infer its components. If we were talking about a bedroom it would very likely that it had a bed. That enables us to define our second corollary:

Corollary 2: we can infer components based on the container name.

Pretty obvious, but now that we have some rules, let’s try to apply them to this next room.

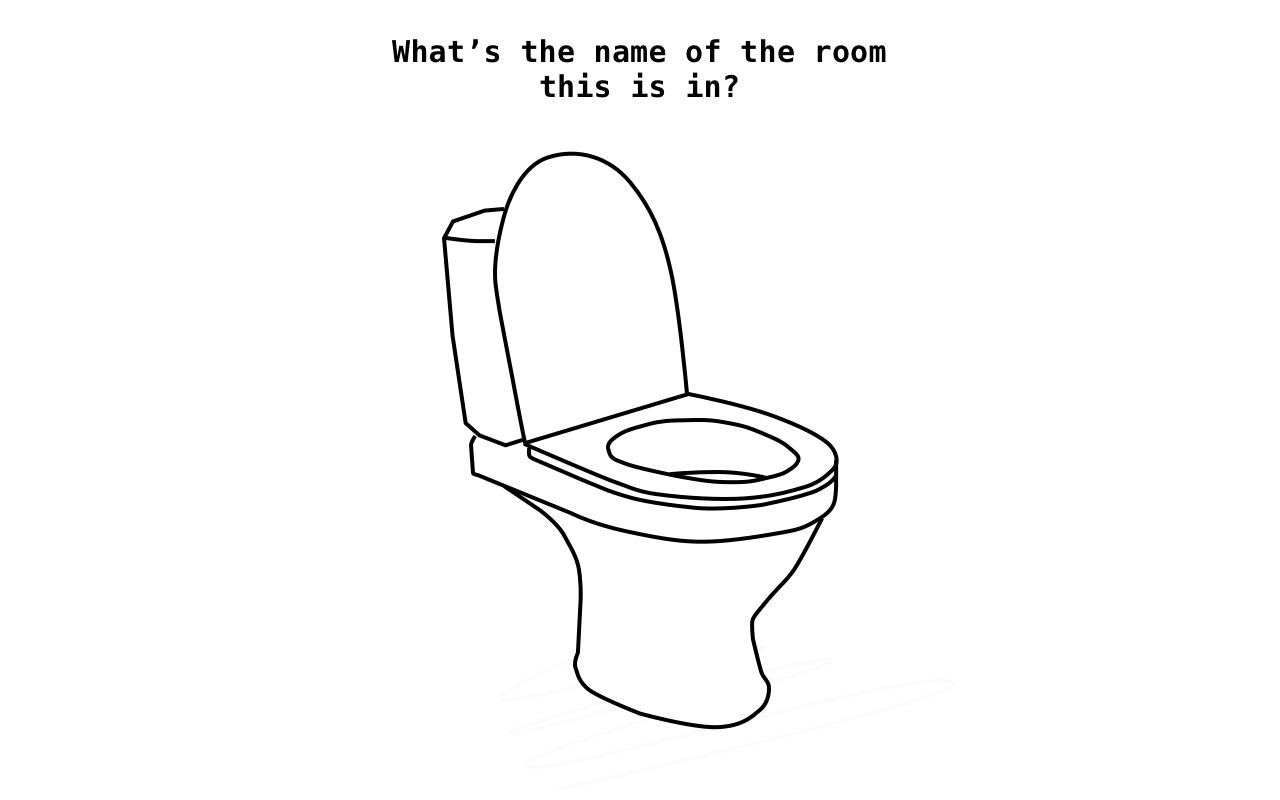

Question 3 of 3

If our system is a house, a bed and a toilet in the same room makes the room definition, by all known western standards, pretty much blurry, foggy. Do you notice how using corollaries 1 and 2 becomes non-trivial to name this room? We could very well name it the Ambiguous Room.

In my experience, most of the time the challenge of naming things results from bad modeling. When the elements in software have been introduced without coherence, naming will be impossible. The developer, with short deadlines, are forced to deliver whatever comes to mind first.

At home, we put together things that have the same function, purpose and intent. That makes organizing easier, whereas by messing with these responsibilities we cannot be sure what the architects wanted or how these objects are meant to be used, blocking flow.

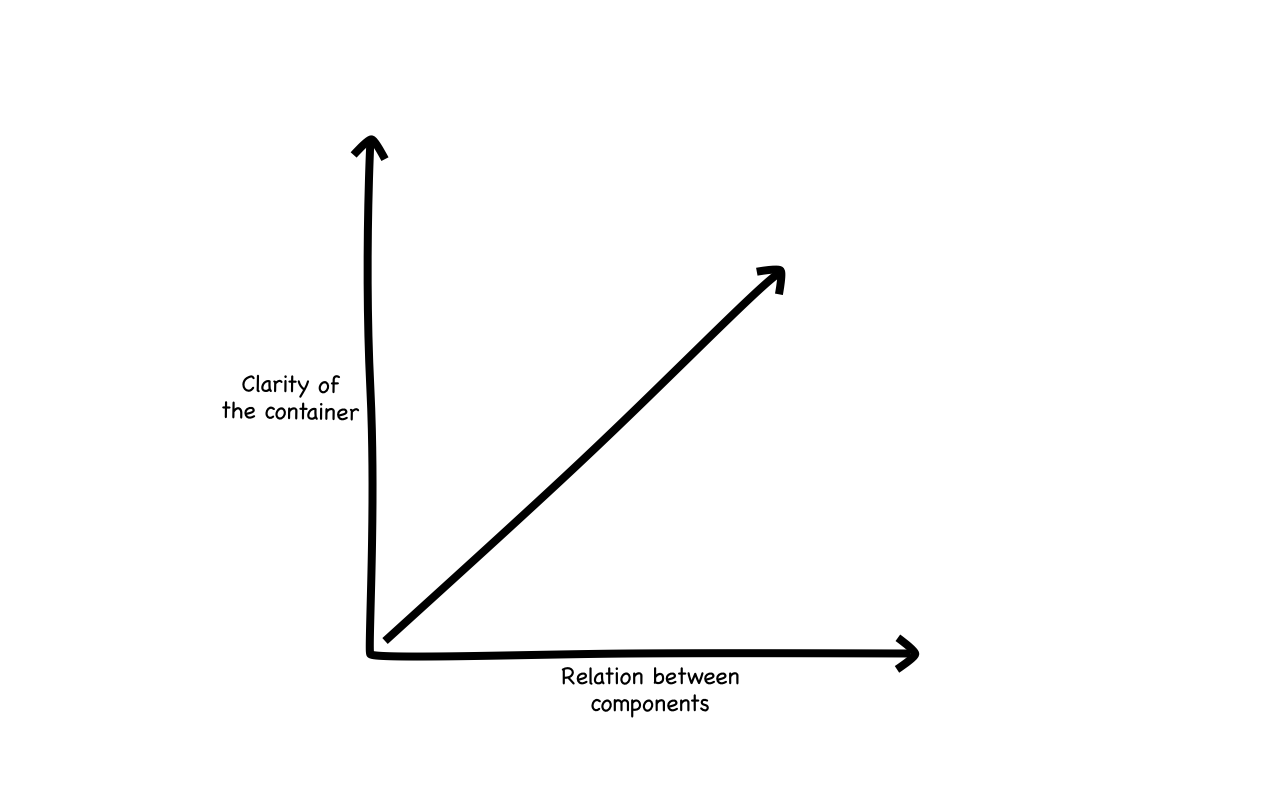

Corollary 3: the clarity with which a container is defined is proportional to how closely related its components are.

This is hard to read, so let’s use a picture:

When components are related, it’s easier to find a good name. When things are unrelated, it becomes increasingly difficult. The word relation here could be their functionality, their purpose, their strategy, their type, and others. Relation on its own doesn’t mean much until we talk about criteria. Bear with me here, and we’ll get to that soon.

Note that these assumptions would flip upside down if our system was a prison, not a house. In that case, the reader would easily identify this room as a prison cell. That leads us to an important definition.

Corollary 4: a container definition is constrained to its context.

This seems obvious when our focus is on the definition of the container, but this surfaces another problem: it is common for systems to leave context undefined. A module represents context, and submodules represent sub-contexts.

When most code is flat, the context definition is missing, preventing differentiation among containers. The cues that indicate that where code should go don’t exist, and so it feels like code is random.

For example, a directory without any modular segregation, with flat classes serving all types of functions, from database manipulation to authentication, custom data structures and view logic, will hide contexts and prevent cues from emerging, resulting in inferior readability.

This creates incentives for developers to add code anywhere because there are no hierarchical cues. As Alan Kay puts it,

Most software today is very much like an Egyptian pyramid with millions of bricks piled on top of each other, with no structural integrity, but just done by brute force and thousands of slaves.

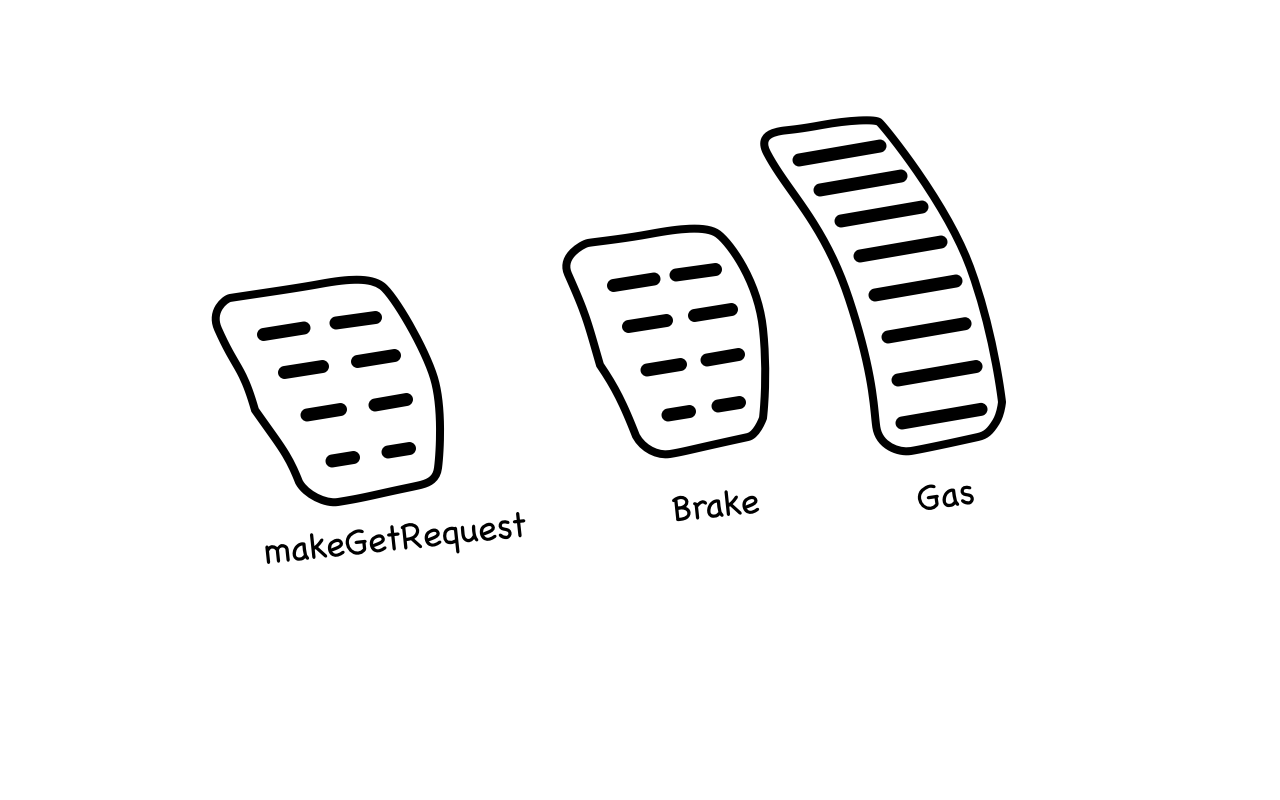

Example 1: HTTP domain and a car

HTTP is a domain and it has requests and responses. If we were to put a component called Car within it, we wouldn’t be able to call it HTTP anymore. In this case, it becomes something confusing.

public interface WhatIsAGoodNameForThis {

/* methods for a car */

public void gas();

public void brake();

/* methods for an HTTP client */

public Response makeGetRequest(String param);

}

Example 2: Coupling through words

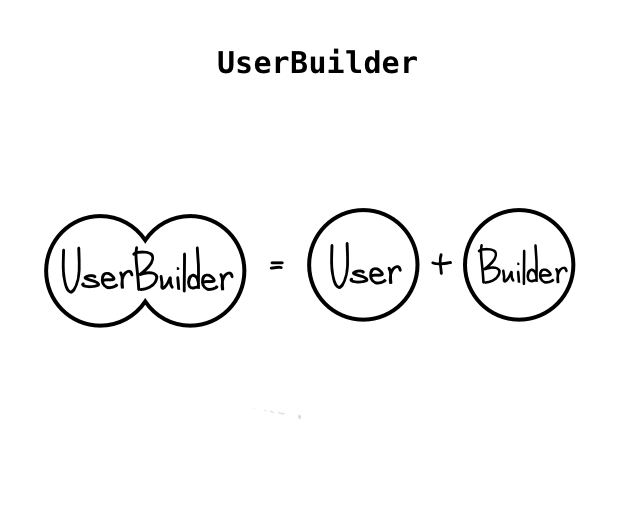

A common pattern is appending Builder and other Er-ending words in class names. SomethingBuilder. UserBuilder, AccountBuilder, AccountCreator, UserHelper, JobPerformer.

Judging by the name, we can interpret three things. First, the verb Build in the class name implies that it’s a function, when in fact it’s in the class title. Functions do stuff, classes embody entities and context. A function is not an entity, and without entities well defined the codebase quickly develops into procedural code because it’s sub-utilizing the class pattern’s original intention.

Second, it has two inner, hidden entities within it, a User and a Builder, meaning a probable encapsulation violation. By that we mean that a User shouldn’t be responsible for generating new Users.

Third, it implies that Builder has access to how a User functions internally because, after all, they’re entangled with one another.

I’ve seen entire codebases littered with this approach. There are complicated patterns that attempt to solve this, like FactoryPattern. Some times they’re useful, but when we have a modeling problem, we better fix it, not bandaid it.

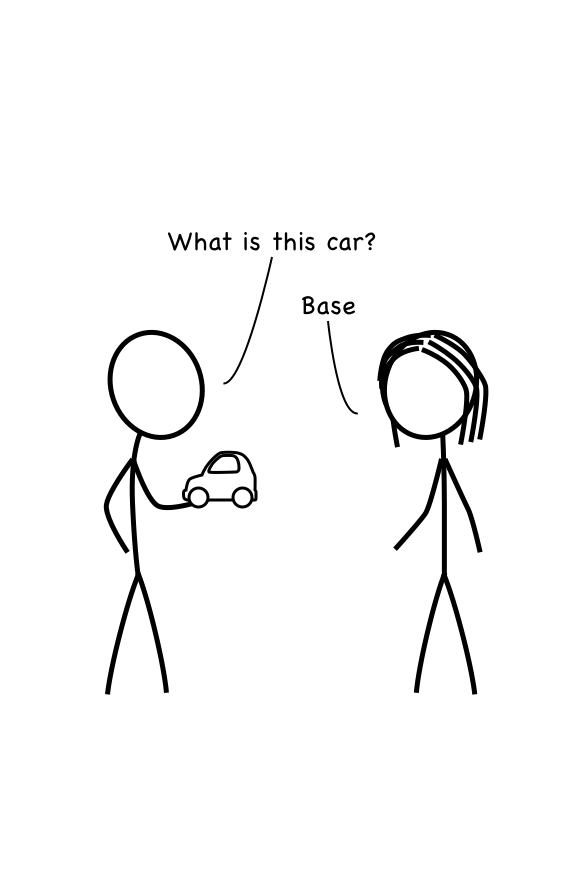

Example 3: Base

Let’s look at a few real life examples. First one, the I18n Ruby gem (only class and method names provided for brevity):

class Base

def config

def translate

def locale_available?(locale)

def transliterate

end

Here, Base doesn’t express meaning. It can configure and translate, as well as figure out whether a locale is available or not. It’s doing a few different, unrelated things.

Example 4: names guiding design

When we talk about how names can guide our design, Discourse has a few examples, one of which interests us.

class PostAlerter

def notify_post_users

def notify_group_summary

def notify_non_pm_users

def create_notification

def unread_posts

def unread_count

def group_stats

end

The name PostAlerter suggests functionalities that alert someone about a post. However, unread_posts, unread_count and group_stats clearly deal with something else, making this class name not ideal for what it does. Moving those three methods to a class called PostsStatistics would make matters clearer and more predictable for newcomers.

class PostAlerter

def notify_post_users

def notify_group_summary

def notify_non_pm_users

def create_notification

end

class PostsStatistics

def unread_posts

def unread_count

def group_stats

end

Example 5: ambiguous names

The Spring framework has a few examples that illustrate components that do too much and, as a result, require names that resemble our Ambiguous Room. Here is one (because this one would be just a bit too much):

class SimpleBeanFactoryAwareAspectInstanceFactory {

public ClassLoader getAspectClassLoader()

public Object getAspectInstance()

public int getOrder()

public void setAspectBeanName(String aspectBeanName)

public void setBeanFactory(BeanFactory beanFactory)

}

Example 6: good naming, for a change

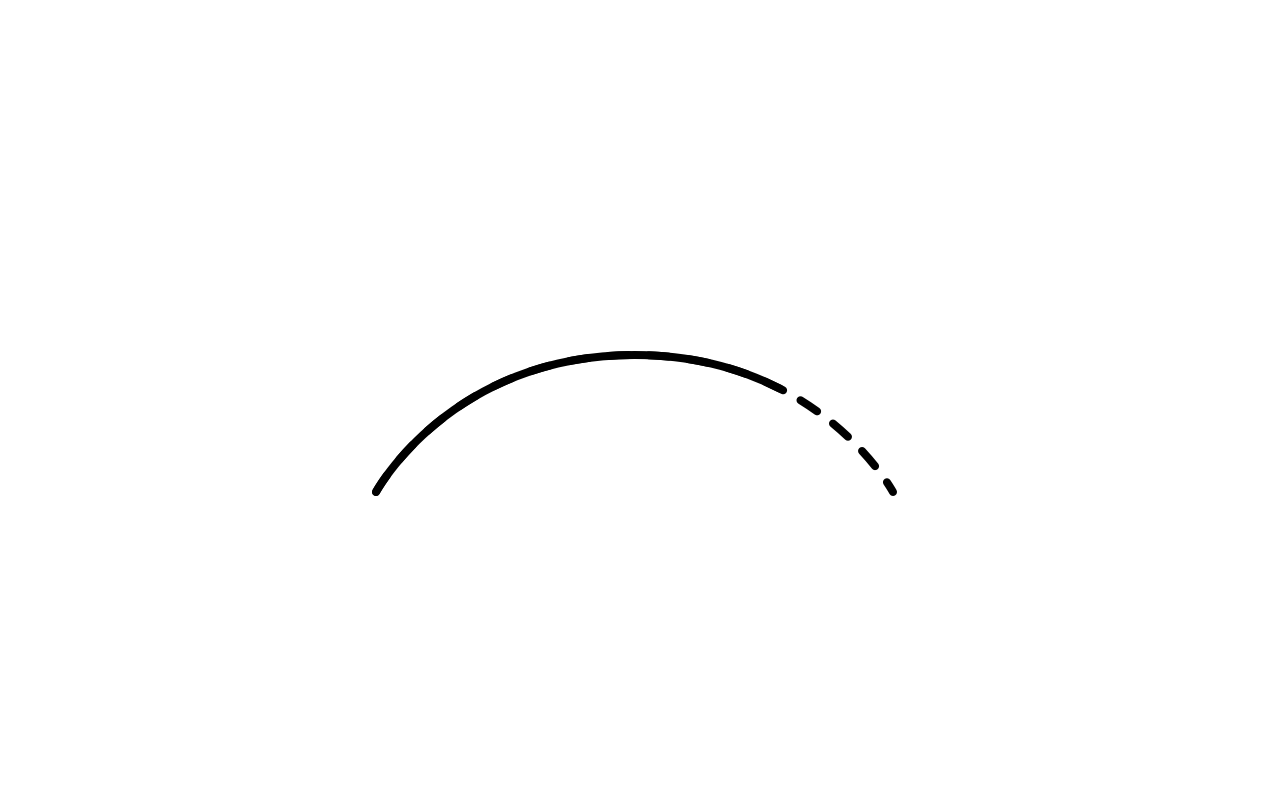

Enough of bad naming. Good naming can be found in D3’s arc, for instance:

export default function() {

/* ... */

arc.centroid = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.innerRadius = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.outerRadius = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.cornerRadius = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.padRadius = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.startAngle = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.endAngle = function() { /* ... */ }

arc.padAngle = function() { /* ... */ }

return arc;

}

Each one of these methods make total sense: they are all named after what an arc has. And what I love about the image below is how simple it is.

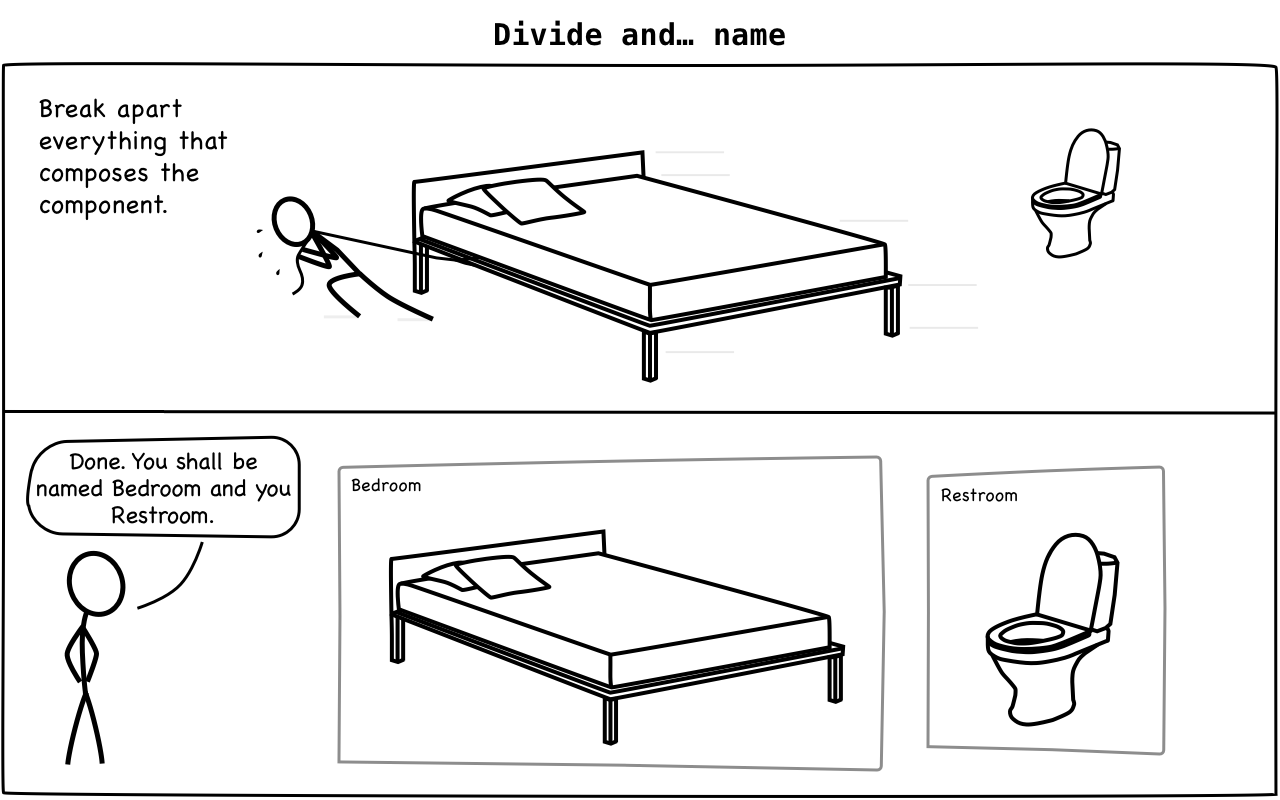

Method 1: Break Apart

When to use: you cannot find a good name for a class or component, but you already have isolated concepts and want to find good names for their groupings.

It consists in two steps:

- identify the concepts we have

- break them apart

In the toilet + bed scenario, we pull apart each different thing we can identify by pushing bed to the left, toilet to the right. Ok, now we have two separate things that we can finally reason about in a natural way.

When you cannot find a good name for something, you probably have more than one thing in front of you. And, as you know by now, naming multiple things is hard. When in trouble, try to identify what pieces and actions compose what you have.

Example

We have an unnamed class containing a request, response, headers, URLs, body, caching and timeout. Pulling all those apart from this main class, we’re left with the components Request, Response, Headers, URLs, ResponseBody, Cache, Timeout and so on. If all we had was the name of these classes, we could fairly sure assume we were dealing with a web request. A good candidate for a web request component is HTTPClient.

When the code is hard, don’t think about the whole first. Don’t. Think about the parts.

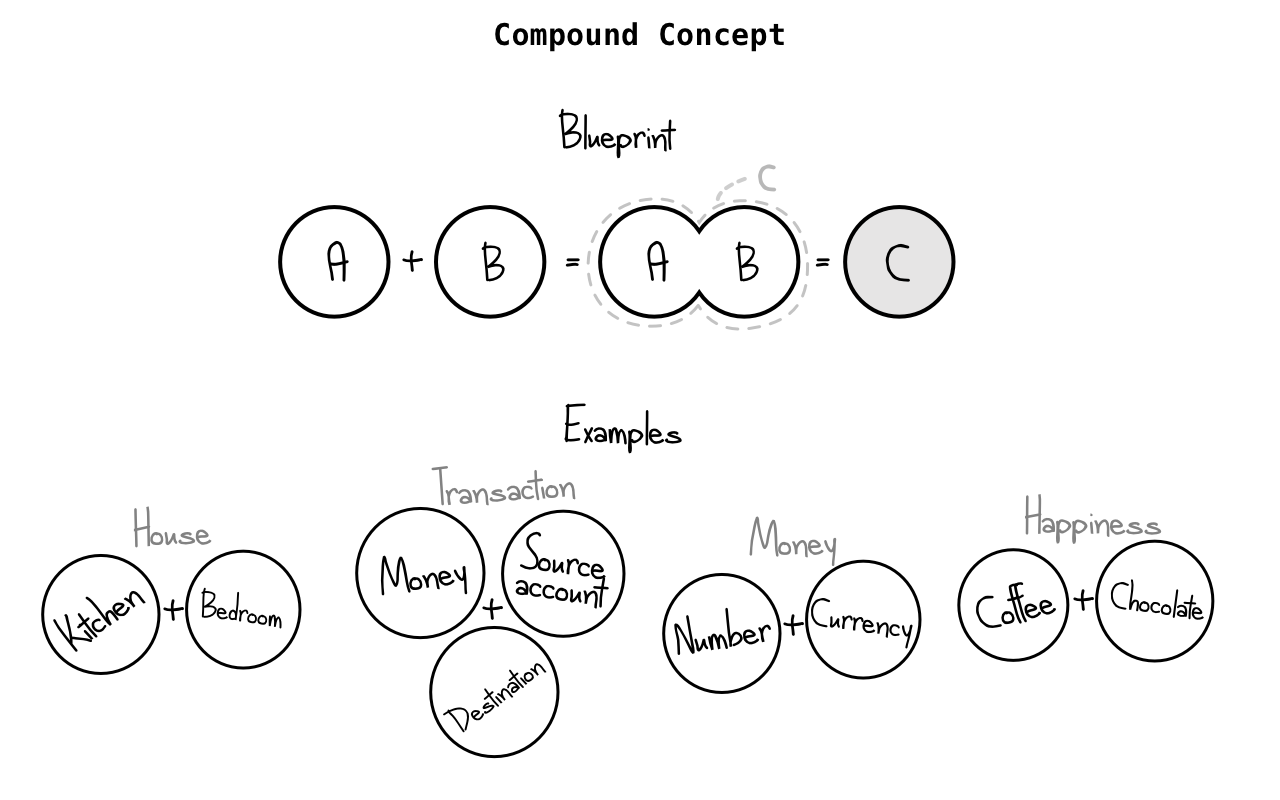

Method 2: Discover New Concepts

When to apply: when a class is not simple or coherent.

Discovering new concepts requires knowledge of the business domain. When software applies the same nomenclatures as the business, an ubiquitous language is established (Evans, 2003), one that allows professionals from different areas of expertise to speak the same idioms.

Example 1: encapsulating components into one new concept

A few years ago, a company was about to lose a big contract. Why? Because the team was slow to ship new features and fix bugs.

This marketplace ecommerce charged students with different rules in different countries with multiple payment gateways. Requirements were fairly complex. When I saw the charge code, PaymentGateway, I was shocked at how complicated it was, with several dependencies, including: User, UserAddress, CreditCard, BillingAddress, SellerAddress, LineItems, Discounts, and more. Its constructor was gigantic and this complexity made it hard to add new rules, as touching one thing broke others, as well as requiring us to change all gateway adapters.

The problem extended beyond payments. Emails were sent to students by having messaging classes aggregating all this data again. Technical support had their own screens with this data aggregated a third time, except that this particular place was using a class called Aggregator (word that means nothing without context). We had to do something to fix this architectural blocker.

To solve the problem, I started with a mind exercise. Here’s an idea of how it went:

Here I am, with these details about things I need you (the

PaymentGateway) to charge for me. If this was a desk, I’d have these papers organized and I’d probably call them Invoices. So what if I created one class calledInvoice, which is nothing more than the aggregation of all these other details, such that the gateway doesn’t need to know how those rules are done becauseInvoicewill? Instead of injecting a million objects, I just hand one over to you?

The Invoice term wasn’t used anywhere. We spent a month refactoring on the side and once we were done, we were able to change the software much more swiftly.

Invoice is a good example of concept that is but an aggregation of data from many sources and the majority knows what it is. The final solution added the Invoice class which alone was injected into the gateways, serving as a facade pattern and hiding other classes.

Good naming is not just about writing beautiful words, but also writing precisely what needs to be expressed that wasn’t before.

Example 2: Pivoting names based on the business domain

In a greenfield, carpooling project, we designed the system from the ground up and during research with other transportation solutions, the appropriate word to describe someone’s journey on a given day from origin to destination was trip, and the group of people was called ride. We published a glossary so the rest of the company could discuss and share the same ubiquitous language.

After launch, our customers always referred to trips as rides. Soon we had problems translating support requests to what had to be done, and after some considerable pain, we decided it was time to refactor trips to rides and rides to carpools. That solved the problems of one company speaking two different languages.

Example 3: levels of abstraction

One person says, move right leg then left leg then right leg, other says walk. Both mean the same, but the latter is said to be more abstract.

Ideally, as the code gets closer to its public API, the closer it tries to match business nomenclatures. As it get close to the database and to the metals, it uses machine nomenclatures that relate to its context. In between, a gradient that goes from more to less abstract.

In one company, a business person would say post Tweet, so a name such as postTweet() would make more sense in a public API than makeHttpRequest(). In a company with a more technical service, the latter would be more adequate.

Second, consider specificity. postTweet() is very specific, whereas makeHttpRequest() is so generic it could be used for Facebook or basically anything involving HTTP. A generic name can be reused easily on the price of being vague. That explains why frameworks code are so different from business software code.

Example 4: generalization

A long ago, a CMS had database tables news, history, videos, articles, pages and other. Most of them had the same columns, title, summary and text. The videos table had extra attributes such as url (to embed YouTube) and history had a date attribute so the page would show a list of historic events by year. All these tables looked like copies, with a few differences here and there, and adding new functionality required rewriting a lot of boilerplate all over again.

I collapsed all those tables into one called contents with a foreign key pointing to a table called sections, which had the list of sections such as news, history, videos and others. Now, one code for contents was enough. Years later, a friend had to write a small CMS and I suggested the same approach. Once the forms for managing content were done, it took 1/N of the time it would normally take to implement anything because for every new section of the same type, it was already done.

Generalizing by giving it another name enables great productivity. News is a Content. Article is a Content. History is a Content. Can all of these share the same attributes? Yes. Survey? No, not a Content.

Method 3: Criteria For Grouping

When to use: when names are good but they don’t fit well with each other.

Components can be grouped by a variety of criteria, including physical nature, economic, emotional, social and, the most used in software, functional. Photo frames are grouped based on emotional aspects, whereas products are grouped based on economic motives. Couch and TV stay in the same room, grouped together based on a functional criteria, as they both have the same function or purpose, to provide leisure.

In software, we tend to group components by function. List your project files and you will probably see something like controllers/, models/, adapters/, templates/ and so on. However, some times these groups will not feel comfortable and that will be the perfect time to reevaluate the structure of your modules.

Example: grouping by strategy

A library for automating documentation operations generates a spec file (i.e API Blueprint) based on code, lints said file (to guarantee is correctly formatted) and uploads to the cloud (i.e S3).

Based on the document format, a variety of subsequent decisions will be made automatically. Choosing API Blueprint will pick up a different linter, a different tester and a different API Elements converter. The key word here to group all of these different functionalities based on one input is strategy. Following that, the library includes a module (or namespace) called Strategy to group together file formats, linters, document testers and storage providers. That enabled the library to separate ordinary operation files like uploaders, parsers and command-line from business core strategies.

Leveraging Contexts

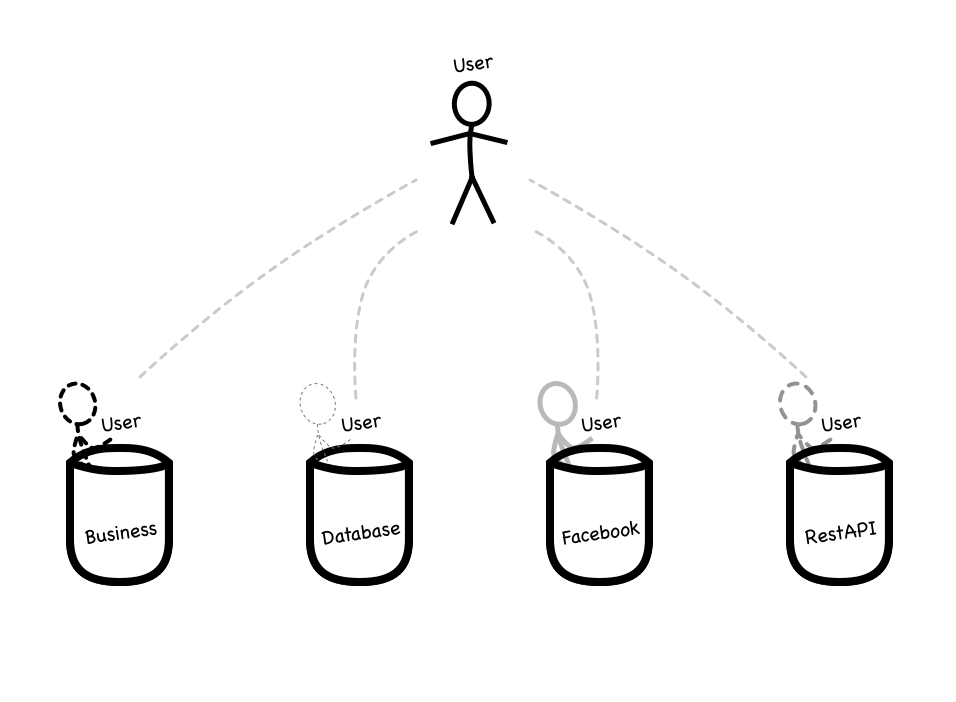

Every app has a different context, and every module within it, every class within them, down to every function. The word User alone could mean user of the system, but also perhaps a database table, or a 3rd-party service credential. lib/billing/user differs from lib/booking/user, but they’re still user.

Imagine that every container, such as a module, is a bucket. Within them, components are insulated from the outer world. You’re free to name those classes whatever you want. It frees the mind from having to find esoteric names for common things.

One strong argument for microservices (many, isolated buckets) over monolithic architectures (one big bucket with small buckets within) is that it enforces constraining responsibilities within each service because now you then cannot easily entangle completely unrelated things with each other. Billing lives inside BillingApp, booking inside BookingApp and so on. In a monolithic architecture, these respective service names could be simple module names, but not everyone has the discipline to keep things tidy.

Example: Namespaces

Mark is building an ad platform that needs to generate hundreds of thousands of ads, then send it to AdWords, Facebook and Bing, all managed through a Graphical User Interface.

Mark starts with an entity called Ad which soon gets bloated. AdWords’ ads have headline_part1 and headline_part2, Facebook’s don’t, while Bing has only headline. He needs to think of a way to split his entity. He ponders about the different contexts and how he could leverage the language’s namespaces feature to express that. He comes up with the following structure:

Adwords::Ad: this represents an ad object in Adwords. It has attributes that are unique to Adwords and the logic can be contained in this class.Facebook::Ad: same as the previous one, except that it has Facebook’s specific requirements and logic.Bing::Ad: same as above.RemoteAdService::Ad: this serves as an interface betweenAdwords::Ad,Facebook::Ad,Bing::Adand the rest of the system. This means that these three class will all have the same public API, allowing the system to leverage polymorphism.Database::Ad: this is the ORM for theadstable. It uses ActiveRecord, DataMapper or any custom solution.GUI::Ad: this represents the attributes required for display of an ad in the UI. It possibly has presentation and internationalization functionality.API::Ad: an HTTP endpoint for an ad will have its own custom attributes, therefore it makes sense that the serialization logic lives here.

Words can mean different things depending on context, and when we leverage context, we can choose simpler words for components. In this example, we didn’t have to do any acrobatic movements to find those component names because they’re all one thing, ad.

Meaninglessness and neologisms

Over the years, names evolve and acquire news meanings. Others come in to fill in holes.

Helper: helpers are functions that support the main goal of application. But then, what’s the criteria to define what’s the main goal of the application? Everything in an application supports the main goal of an application.

In practice, they’re lumped together in an unnatural grouping to provide reusability for some miscellaneous, commonly used operation. They tend to suffer from Feature Envy, where they need to access another component’s internal data to work. They’re an excuse for things that one can’t find a proper name.

Base: classes named Base were a convention a long time ago in C# to designate inheritance when lacking a better name. For example, the parent class of Automobile and Bicycle would be Base instead of Vehicle. In spite of Microsoft’s recommendations to avoid that name (Cwalina, 2009), it infected the Ruby world, most notable via ActiveRecord. To this day we still see Base as a class name for something that developers cannot find a name for.

Variations of Base include Common and Utils. The JSON Ruby gem Common class has the methods parse, generate, load and jj, for instance, but what does common really mean here?

Tasks: there is a wave in the Javascript community to call asynchronous functions, tasks. It started with task.js, and the term became used even when that original library wasn’t present.

Does everyone in the team understand it? Then it’s fine! But what about when someone new joins the team and nomenclature that exist since the 60’s are thrown into garbage?

I worked in a project where the name of a class was, guess it, Atlanta. Yes, Atlanta. Fucking Atlanta. No one knew or could tell me why that was called that way.

Communicating

“Reality exists in the human mind and nowhere else.” George Orwell

I believe the practice to excel at communication to be an act of altruism, and the effort we put into improving our skills is correlate to how much we care about other people. We want people to understand easily, we want to remove the friction and barriers.

Secondarily, we want others to understand us. By accepting that a Receiver getting a message is a Sender’s responsibility, we build an empathic environment. It’s a win-win situation. There are no excuses for not deliberately practicing our communication skills - unless you live in the jungle.

With writing, we optimize for reading and the exercise in empathy can be exhausting. But, as everything in life, proficiency only comes to those who practice.

Bibliography

Cwalina, Krzysztof. 2009. Framework Design Guidelines: Conventions, Idioms, and Patterns for Reusable .NET Libraries, Second Edition. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc. 206.

Evans, Eric. 2003. Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software. Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional.